Join Dr Kate with special guest Professor Alistair Paterson as they discuss the extraordinary history of the northwest, and some of the special documents held by the State Library that are vital primary sources for new research about the history of collecting in WA.

This conversation covers the letters of William Shakespeare Hall and the memoir of John Slade Durlacher, the pastoral and pearling industries of the northwest, and confronting the difficult histories in our collections of the colonial frontier.

Recorded live on ABC Radio Perth on 15 October 2021.

Transcript

BEGINNING OF INTERVIEW

Christine: So today, taking you to the North West of our state. It’s a place which has produced some of the best treasures in our state’s historical collection.

Dr Kate Gregory is the Battye Historian from the State Library of WA.

Welcome back Kate.

KG: Thanks Christine.

Christine: And I have Professor Alistair Paterson who is an archaeologist from UWA who has been up late talking to the ABC on Night Life.

Hello Professor.

AP: Hi, welcome, thanks.

Christine: Thank you for coming on.

Now, Alistair you’ve worked for many years in the North West of our state. Why is this part so extraordinary in terms of treasures and collections?

AP: The amazing thing about the North West and it hit me as soon as I came here from over east 20 years ago, is that you can tell the whole story of Australia just in this place and so few people know about it elsewhere, so it is an amazing 400 years of kind of shipwrecks and colonial histories and just wonderful stories, so it’s a fabulous place to work.

Christine: That’s a great Google review, just quietly [laughs].

I’ve never heard it said so succinctly but it really does summarise it all.

Kate, what would you add to that?

KG: Yes, look I would agree with Al and I suppose from the State Library’s perspective and why it’s so exciting to work with people like Alistair, is because we have the primary documents. We have got the archives within our collection that speak to these stories of the North West that Al is busy uncovering in a lot of his archaeology work. So the sort of work that Al does in sort of reviewing the archaeology, doing new archaeology, discovering the archaeological evidence, we can think about the State Library’s collections as also a form of evidence and this is the documentary evidence so we can put the two together.

Christine: Yes.

KG: And tell some incredible stories. So, yes.

Christine: A jigsaw.

KG: That’s right.

Christine: Now, can you tell us about the William Shakespeare Hall materials. Why are these so valuable?

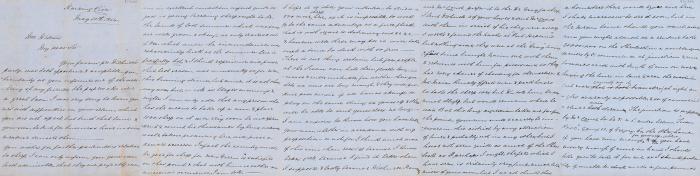

KG: Oh well look, I think apart from the extraordinary name William Shakespeare Hall which sort of throws a lot of people. Who on earth is William Shakespeare Hall? But he was of course one of the very early pastoralists in the North West and in fact what we have in our collection for instance is one very special letter that was written in 1864 ... in May 1864 by William Shakespeare Hall to John Wellard and it’s really one of the first letters ... European letters ... correspondence you know from the North West and he was involved with Andover Station and Al is very much familiar with Andover Station and ...

AP: Well I think we both have been there haven’t we?

KG: Yes.

AP: Yes, we’ve toured a range of stations. We looked at those early stations ... the sheep stations around Roebourne several times and Andover is one of those and it’s an extraordinary ruin like most of these and there’s these rich archaeological records around them of Aboriginal camps and rock art and there’s the attempts to set up these sheep stations and so, yes very, very special lines of evidence and you need the historical sources. When you have a letter like that, that explains what was happening on a given day, it’s fabulous to actually bring them together.

Christine: Yes, I bet.

And the State Library also holds a significant manuscript which has been important to your work - the Durlacher manuscript. What is this document?

AP: Yes. Durlacher is really interesting because so few observers in that colonial world spent a lot of time observing Aboriginal people, so he spent a lot of time mainly observing Ngarluma people in and around the islands and one of the ... just an example of something you’d get from that is that he was on the islands out in the Dampier Archipelago on West Lewis Island where there is this wonderful remains of this bizarre sheep station and we’ve often wondered what went on there and he tells us that Aboriginal people were out there when he was there and so if we didn’t have that, you wouldn’t actually understand the ways in which people continued to use the islands well after Yaburara people went through the Flying Foam massacre which was a horrific event so it’s really interesting to have those kind of collaborations about what was happening in and around the colonial world and that’s one example of it.

Christine: Yes, how unique is it?

KG: It is. I think from my perspective, being able to look at these documents with fresh eyes is really, really important and I guess each generation of researchers will bring a different set of questions to these documents and it’s very important to use it as a primary source; to look at it with that fresh perspective, so that’s why we get excited by new researchers like Al coming along and having a look at these documents. The document itself is difficult. It’s a difficult colonial document.

Christine: Why is that?

KG: In some respects, it reflects the racist views of the time. You know, modes of thinking that are long discredited, that are difficult reading for a 21st century reader in some respects but nevertheless it’s a rich source of information. There are word lists, mainly Ngarluma I think word lists, and so really kind of important historical document from that perspective.

Christine: When you say word lists...

AP: Yes, writing down the names of objects and places as well. And so these things can be re ... taken back to the place where there were for instance ... observations were made or collections were made and people have a kind of a bit of an understanding of how people were operating at that time because ... right, so these sheep stations which are romantic ruins on one level, they represent the ways in which Aboriginal country was taken and so these are established when we say that Aboriginal camps were around them, that’s because of all of the labour was Aboriginal people who made that industry tick and the pearling industry as well, so they represent the colonial world with all of its dark sides as well as what emerges in the present so it’s a kind of complicated crossover landscape of history as well.

Christine: Yes, you articulated so well because it is quite complex. How has the North West connected us to the rest of the world then?

AP: I find that the amazing thing is that every big industry ... we think of the industry of the North West now but it really started a long time ago so we have the Guano industry right, so those islands were all mined along the West Australian coast and phosphate went everywhere in the world. Massive ships from America and everything and off the Kimberley coast. And then you have the whaling industry, you know ships from all around the world harvesting you know ... that’s why the whale populations are so diminished along the West Australian coast. Then we have the pearling industry which is West Australia’s largest export industry so it just keeps on going. There are so many phases of kind of industrial history to be thought about with the North West.

Christine: Yes, very true.

20 minutes past two on ABC Radio – Perth and WA.

I’ve got Dr Kate Gregory, Battye Historian from the State Library in the studios and Professor Alistair Paterson, Archaeologist with UWA. So can you tell us about the project you are working on at the moment, ‘Collecting the West’. What is the focus of that?

KG: Yes, so look, ‘Collecting the West’ is a really exciting collaboration between our state collecting institution; so it’s the State Library working with the WA Museum, the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the British Museum and UWA and Deakin University and what it aims to do I suppose is uncover the sort of histories of collecting in Western Australia and not only that, how Western Australian material has been collected across all types of disciplines and circulated in global collecting networks and it’s ... yes I think we’re into probably the fourth year or fifth year…

AP: We are, yes.

Christine: [Surprised] Ohhh.

KG: Of research and some amazing stories and amazing material coming to light through this research.

Christine: So what are some of the objects, specimens, stories, tell us.

AP: Well we could start with one of our favourite objects right from the start was William Dampier’s collection. So Dampier was the first Englishman to arrive in Australia, right, and on his second expedition, he visited Shark Bay and the Dampier Archipelago on the Kimberley coast and he made collections. He was famous as being a pirate, but really he should be famous as a naturalist. So he loved the natural world and the plants and the animals. He drew them, he collected them and they ended up back in England. And so if you go to Oxford today, you can go into the botanical collection at the University of Oxford and you will see these large sheets of cardboard and on them are plants collected from Shark Bay and the Dampier Archipelago, so and they’re the oldest surviving objects from Australia outside of Australia that have been collected.

Christine: So how old are they?

AP: Well they would be from his second ... so 1699.

Christine: [Astonished] [Gasp] That’s ... that ... I had no idea that was the case.

AP: They are amazing.

Christine: They are such old specimens. And wouldn’t you be ... it would be terrible to be the one that kills them [laughs]. You know because somebody has got to keep those alive [giggles].

AP: Well they’re actually the plants, right so there are ... so they’re preserved ... so they’re the type for those plants. And so some of them have actually been brought back to Shark Bay a few years ago. The University of Oxford organised that I think with the herbarian here. So they’re ... they’re quite famous.

Christine: Ok. So are they ali ... but are they alive, or are they just ... I don’t understand.

AP: I am afraid they have ...

Christine: They’re not alive.

AP: Long gone.

Christine: Ok, alright sorry.

We were talking about it in the office earlier on. We were like, “These plants are still alive after 400 years”.

Al: [Laughs]

KG: [Laughs]

Christine: Ok, no, no, ok fair enough. Ok but you’ve got the material you need to ...

AP: Absolutely.

Christine: ... create them again.

That’s why I’m not a scientist. I’m just a presenter and just making sure I get that right.

So some of the other objects and/or specimens. How about you Kate?

KG: Well, there’s all sorts of things. Something that we have in our collection which is pretty special and bearing in mind we have the documentary heritage. So we have the letters, the archives, the diaries and something that we do have are some letters and accounts from Georgiana Malloy who was of course involved with collecting early botanical specimens from the South West.

Christine: Yes, have you mentioned her on here before?

KG: And sending ... no we haven’t actually had a good discussion about Georgina Malloy.

Christine: Yes, tell me more.

KG: We must do that.

Christine: Yes, yes, yes.

KG: So yes, she collected a lot of botanical specimens from the South West and sent them. They’ve ended up there now actually at Kew - Kew Gardens in the UK. So, and they’re very important collections. And so we have letters and diaries and accounts written by her. They are very ... they’re difficult documents because they are very hard to read. A lot of them have been transcribed but they are ... they’re fragile and they’re written in pencil and they’re very hard to read and there’s often cross-writing in some of these letters where to conserve paper, they were writing both ways. So ... it becomes very difficult to decipher but really ...

Christine: Both ways?

KG: Yes, both ways, yes which was a common thing really in the colonial world because paper was so scarce and they had to be mindful of what they were using so, yes, that’s one example but I think yes ... to be able to again ... I think what’s exciting is to be able to through this research, trace where West Australian collections material has ended up worldwide and start to put together a picture I suppose of Western Australia being a very kind of globally connected place from the colonial period.

AP: Yes, absolutely. I mean one of the fantastic things about Western Australia, is during the 1900’s all around the world, people invented and opened museums and archives and art galleries and so there was this great global demand for things that were unique, right, because there’s no internet so your museum is your internet. So you walk in there and you see the world, right and so you needed materials from Australia; geological, natural histories, so people would go to Kew Gardens and look at a stump of a piece of jarrah and gaze at it and touch it and go, “This is an extraordinary thing” right, because they for them, they are looking at this materials (before plastics and all these things) and they were really excited and equally, Aboriginal material was in incredible demand around the world and so a lot of material was being hoovered up from the landscape by collectors and through the museum and I guess the colonial government exchanges were being made so there’s this great global circulation of materials.

Christine: [Sighs] So I mean, what do these collections say about WA as a place? What would you say?

AP: I think one of the most interesting things about place is that quite often things end up in collections. Say you go to Scotland right and Edinburgh, and you see a hair wallaby or whatever it is but if you look behind that and start to investigate and do research, you can actually explore the ways in which it was collected from Bernier or Dorre island and the history of that place at the time and so when the expedition went there and the Aboriginal people they met there who were there as part of the lock hospital and it becomes much more embedded back to the place it was collected and the context and the people. I think for me that’s a really important part of WA’s history through collections.

Christine: Mmm. Would you agree?

KG: I do and I think also that now today, a lot of work is going on to reconnect these collections with communities; not only through repatriation work, but also through digital return and even just through being ... sharing the knowledge and handing back, so there’s a lot of work I think around collaboration with communities to look at rehabilitating these collections and making sure that communities know where they are, where they’re held and that’s really important because collections do inform and shape identity and I think that that’s part of what the role of the State Library and these other collecting institutions is; for not only reflect the society, the community, but also it’s kind of a shaping of what WA identity actually is really. So that’s what our collections can do today and it’s ... yes.

Christine: 25 minutes past two.

If you have just tuned in, Dr Kate Gregory, Battye Historian from the State Library with me and Professor Alistair Paterson, Archaeologist from UWA.

I’m very keen to get your response to Tony from Denmark if you don’t mind and when we’re going to bring him in, Tony what would you like to say?

Tony: Yes, hello and I’ve got tremendous respect for the ... obviously for the tremendous work your two people have done in this field but you just talked about their identity of West Australia and I think that’s the problem that I have as someone who is nothing like as aware as these two people are but have got a reasonable idea of the history of the colonial pastoral industry and the tremendous damage to the landscape that created and then the massacres that went along with that and I find it quite difficult to have any respect for that sort of early culture and the early European culture and I was just wondering how you two manage to ...

Christine: How do you navigate that?

Tony: Yes.

Christine: Yes, it’s a ...

Tony: I’d find it very difficult.

Christine: It’s a good question ... it is a good question and it’s something that I have felt during these segments as well. I mean, yes if you could respond that would be great.

AP: I think difficult is the right word and that’s true for much of colonial Australia. I think of projects that really try to reveal the nature of the colonial world as being a really important part of reconciliation. I do know that many of the Aboriginal groups that I have the privilege of working with ... there’s a great interest in for instance the pastoral industry because many of the older people grew up in that industry and they have a complicated relationship with it but equally it’s not something that can be just ignored because it’s very much an important part of who people are in the regions and around Australia so I do ... I certainly understand the complexity of it but we do need to look backwards I think to actually understand where we’re going in terms of reconciliation and thinking of our bright futures as well.

Christine: Yes, what would you say Kate?

KG: Yes, look I would agree and thank you for the question because I think it’s something that we grapple with professionally everyday and I think that this is a difficult history and our collections are absolutely scattered with evidence of this difficult history and I think it really comes down to this work towards collaborating with communities, looking at the custodianship arrangements around collections and coming up with new frameworks that might return collections or digitally return collections to communities and I think it is about really acknowledging the past and acknowledging that complexity and it’s truth telling as well.

Christine: Yes, it’s so important. I wonder what our First Nation’s listeners are thinking right now. You can add to that as well: 0437 922 720.

So look, are any of these things that we can go and see online?

KG: Well, yes thanks to the wonders of the State Library catalogue and our digitisation. Yes, so that William Shakespeare Hall letter is fully digitised and that’s available to view through the State Library catalogue so people can just search ‘William Shakespeare Hall’, memorable name and it will come up and you can have a look at the letter. His handwriting is actually fairly easy to read so, yes. And the Durlacher manuscript ...

AP: Kind of, kind of ... yes, search.

KG: [Laughs] Once you get in to that 19th century ...

Christine: You are probably quite fluent in that font ... [laughs]

KG: [Laughs]

AP: Yes, it’s always so great to go to ... as part of Boola Bardip – you can actually go to Hackett Hall which is of course ...

KG: Absolutely

Christine: Ah yes

AP: ... the original library and there’s a set of cases there that the project was involved in collaborating with WAM on ... and they tell the story of collecting as well so ... it’s not open all the time but if you do get a chance to have a look at the old Hackett Hall collection cases, there are some great stories there.

Christine: Yes, it’s pretty cool.

Well thank you both for coming in, especially after your night Professor, I appreciate it.

Thank you so much for your time.

AP: Thank you very much.

KG: Thank you Christine.

END OF INTERVIEW